Cancer is the leading disease-related cause of death among children.

My journey of awakening: A few years after receiving an MBA, I earned my license to sell health insurance. Then I worked for three years as an independent agent, representing four large health insurance companies (Blue Cross, United Health, Tufts and Aflac), and I read a lot.

I read health articles about increases in obesity and incidence of autism, ADHD and diabetes among children. Having a father suffering from heart disease and a mother-in-law fighting stage 4 cancer, I also read about these diseases. And, I came to understand how the increasing usage of medical services was driving up insurance costs.

As a number cruncher, I analyzed the double-digit increases in premium costs year-over-year. These increases surpassed inflation and pay raises, by an order of magnitude in one client case that I clearly recall. Higher insurance costs were placing a greater financial burden on small businesses and their employees. This translated into more stress and more dis-ease. I envisioned our economy being pulled into a downward spiral.

The medical insurance system was an economic disaster in the making, and, in good conscience, I could no longer participate in the “system.” I left my job in medical insurance to work with urban school children in “out of school time” (OST) programs, with the intention of helping “insure” their long-term well-being through physical activity, healthy behavioral habit development and social-emotional learning, through fun activities, mostly outdoors. I sought to address the root cause of poo health.

During my first summertime youth enrichment program (2012), I witnessed the highly-processed, starchy foods being served for school breakfasts and lunches, including sugary cereals, mealy apples and gluey white bread sandwiches that stuck to the roof of the mouth. The sandwich had one wafer-thin piece of process meat and no lettuce. I took one bite and threw it in the trash can.

My youth work experiences compelled me to write articles about children’s health for a local magazine, Natural Awakenings, and my own awakening evolved. The revelations kept coming…

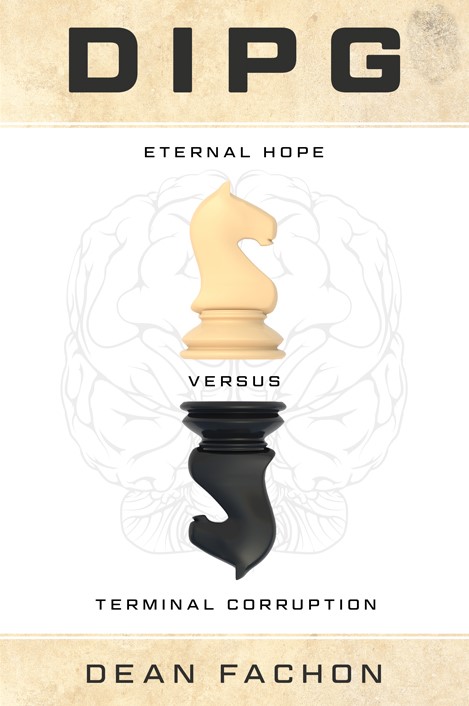

And WHOMP! In 2016, the most unthinkable happened. Our teenage son, Neil, was diagnosed with terminal DIPG brain stem cancer. The oncologist told him he had three months to live, maybe six, if he were to undergo radiation. Neil, my husband and I sat there in disbelief. How could this possibly have happened to an athletic child who had been perfectly healthy one year earlier?

Statistically, the DIPG diagnosis had a one in a billion chance of happening to any child, healthy or immune-compromised. The oncologist could not say what caused DIPG. She conducted a physical exam, and she asked a few questions. She asked Neil when he’d had his last bowel movement, and he could not remember. One week? Two weeks? Yikes! I got stuck in that moment, while the oncologist breezed on ahead with more questions.

Finally, the doctor delivered her recommendations – dexamethasone, a tissue biopsy and radiation therapy (drugs, surgery, radiation) – “standard of care” for DIPG. Clearly, she had no schooling in gut health and nutrition, and this was a blinking yellow light for me. Caution! Caution! Slow down! Wait. Stop right there!

Thus began our real journey of awakening. Stay tuned for additional blog entries, and check out our book.